Helping Neighbourhoods Walk to School

The Challenge:

Today, fewer and fewer students are walking or cycling to school. From 1986-2011, the rate at which Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area (GTHA) students 11-13 years of age were driven to school doubled, according to a Metrolinx study. At the same time, the number walking and cycling fell from 62% to less than half.

As the province reports, this decline in levels of physical activity has significant implications for the health of the region’s youth, leaving our students susceptible to diseases such as diabetes, heart disease and cancer. Encouraging kids to use active transportation at a young age does not just benefit them now; the study suggested that it helps them develop healthy habits that last through the rest of their lives.

Walking to school also has other, less obvious, positive effects on children and youth. In 2016, Rod Buliung, the lead researcher on the Metrolinx study, told the Globe and Mail that walking is also associated with better academic performance and socialization. When kids walk to school with parents or guardians, it provides an opportunity to connect, to discuss their coursework, and to talk through any challenges they may be facing at school. It is also a chance to talk and socialize with friends outside of the direct school environment.

There is an additional benefit to encouraging more walking and cycling to school. With more students being dropped off at school each day, there is an increase in car traffic around school zones. While drivers arrive from many separate locations, the school is the focal point, where car traffic converges for a brief period each morning and afternoon and then disperses. Research suggests that this increased traffic creates dangerous situations and may lead to more collisions with pedestrians and cyclists.

Increasing Active Transportation Through Safer Streets

Working with local partners, Civicplan undertook a study of four schools spread across the city of Hamilton — two urban and two suburban — and made recommendations on how to improve active transportation. A key observation across all schools, regardless of location, was an interest by parents and school officials in facilitating more walking to school. However, in all locations the primary factor that needed to be addressed was street safety.

Decreasing danger from traffic congestion is not the only factor at play in encouraging active transportation to school. Promoting a culture of walking and cycling, including walking school buses, bike programs and other initiatives, is important for helping develop active habits. This can extend to kids who are differently abled or who have challenges walking as well. That said, the first step to encouraging students and parents to walk and cycle is ensuring the routes they will take are safe for people of all abilities.

Engage and Observe

In the Hamilton context, the first step of the active transportation study was to engage with the schools by meeting with each principal to learn about their perspectives on the issues and their areas of concern. This feedback was invaluable, as the principal has the on-the-ground knowledge and perspective that cannot be gained through just a few visits to a school. School populations are diverse and gaining an understanding of some of the special needs of students can help inform an understanding of active transportation challenges. This feedback informed the observation phase and highlighted some of the specific issues facing students.

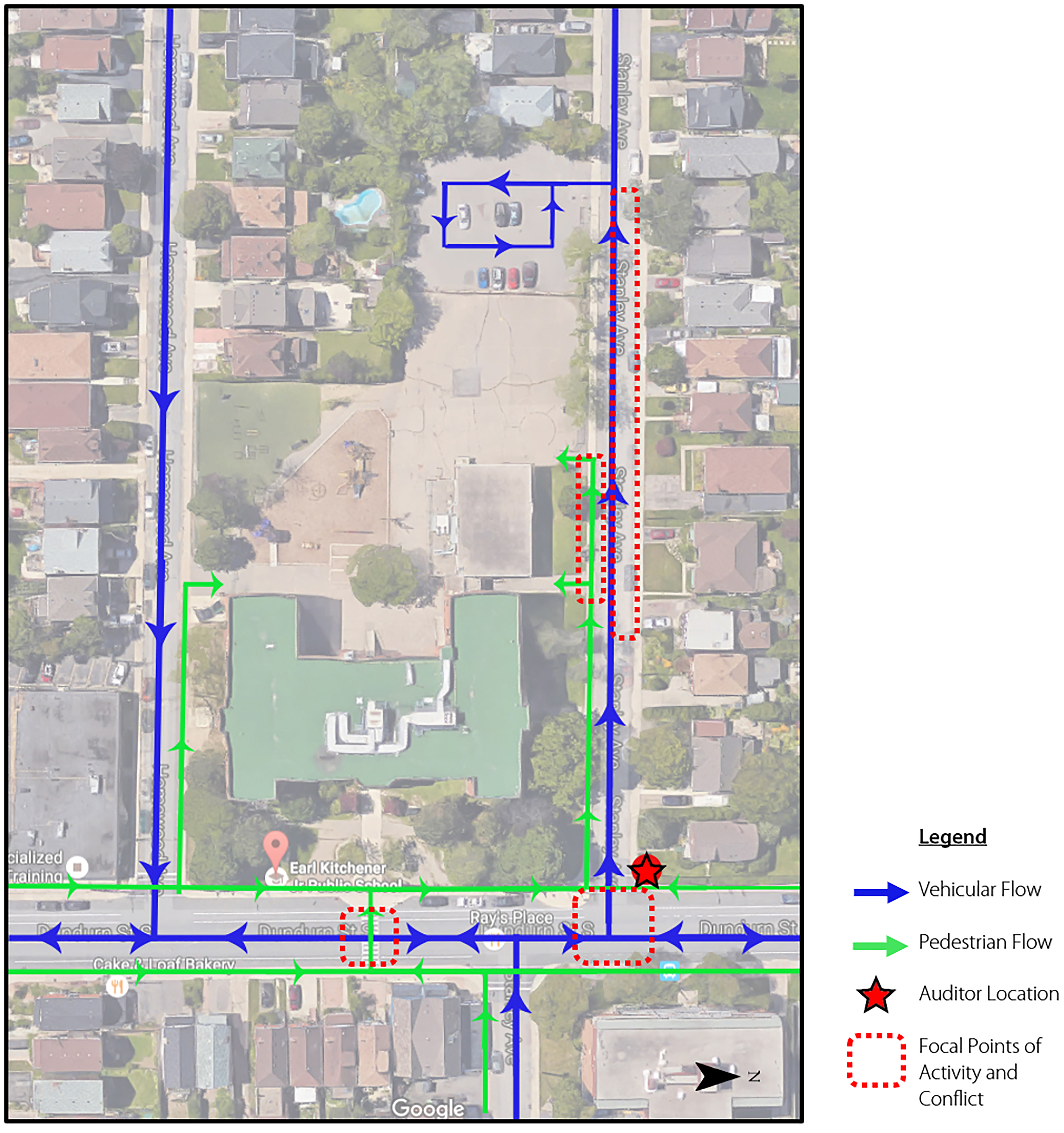

Observation was the next step, which began with an inventory of the school and surrounding public infrastructure. For example, are there bike racks and bike lanes? What sort of pedestrian and vehicle infrastructure is available (e.g. crosswalks, kiss and ride drop offs)? Once this information was mapped out, the transportation patterns at each school during the morning drop-off time was observed.

Central to this was observing the flow of students into the school, including pedestrians, cyclists, and drivers. Some surprising and unsafe practices were witnessed: cars pulling onto the sidewalk, double or triple parking, and crossing guards regularly dodging cars. It was clear from these observations that students regularly faced unsafe conditions due to the heavy flow of vehicles into the school site.

In the final phase, a series of recommendations were presented to help increase active transportation to the school. These recommendations addressed the pinch points and problem areas that were observed, often resulting from the nexus of car, foot, and bicycle traffic all using the same points of access to the schools at once. The goal of these recommendations was to provide actionable interventions that reflected the unique conditions of each school.

A general observation for all schools was that a community solution was often required. Different stakeholders, such as the municipality, school board, individual school, and parents, all had a role to play in the community solution. For example, municipalities have the jurisdiction over street improvements on public property, such as cross walks and bike lanes. The schools are responsible for configuring infrastructure on school property to encourage more active transportation, such a providing bike parking and limiting car parking. School boards can help by changing school start times to allow parents time to walk kids to school before going to work. Finally, parents and caregivers have a responsibility to help make walking to school a daily habit.

Conclusion

Increasing active transportation to schools is one concrete way to improve students’ levels of physical activity. Addressing issues related to transportation safety around schools ensures that neighbourhoods become healthier and safer for both pedestrians and drivers. In the Hamilton study, regardless of location of the neighbourhoods, urban or suburban, the desire to increase walkability was similar. However, each school in each neighbourhood has its own unique circumstances requiring unique solutions. Through engagement with stakeholders and observing how a neighbourhood comes to a school each morning, the specific needs and conditions of each school and its surroundings can be identified, providing the feedback decision makers need to create safer, healthier communities.

This article was originally published in Our Schools/Our Selves from the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives – Helping Neighbourhoods Walk to School: Civicplan