The Right to Play in Our Public Spaces

We could build better neighbourhoods by focusing on how and where kids have the most fun.

Kids playing tag, a street hockey game, hopscotch on the sidewalk. These could all be scenes from a commercial promoting physical activity or selling sports apparel. They equally call to mind common ideas about neighbourhood play, but is it an accurate reflection of what is going on today?

To know where kids play in a neighbourhood helps us figure out how well their community is designed. Is there a local park where families congregate? If so, what do they do when they are there? Are there places for structured play like a soccer field or basketball court, and are there any spaces for unstructured play? Beyond a formal park, what other spaces, both public and private, are used for play in neighbourhoods?

The importance of unstructured out door play is well known. For example, one study from Statistics Canada suggests that for kids aged 7 to 14, outdoor time was strongly associated with increased moderate to vigorous physical activity, higher step counts and decreased sedentary time. Also, each additional hour spent outside was associated with 13 fewer minutes of sedentary behaviour per day.

For kids aged 5 and 6, each additional hour spent outdoors was associated with an additional 10 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity and an increased likelihood of meeting physical activity guidelines. Overall, children who play outdoors after school take approximately 2,500 more steps daily.

For kids aged 5 and 6, each additional hour spent outdoors was associated with an additional 10 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity and an increased likelihood of meeting physical activity guidelines. Overall, children who play outdoors after school take approximately 2,500 more steps daily.

In terms of challenging sedentary practices in children, supporting and encouraging opportunities for safe, free, unstructured active play, especially outdoors, may be one of the most promising, accessible and cost-effective solutions to increase children’s physical activity in Canada.

At Civicplan, we set out to begin a neighbourhood discussion on this issue through the design and development of an engagement tool that records how and where people play in the community outside of school hours. Partnering with Public Health Services at the City of Hamilton, and with funding from the Ontario government’s Healthy Kids Community Challenge, the team designed and implemented a pilot project targeting a typical suburban neighbourhood in Hamilton.

Lisgar neighbourhood is located on the east mountain in the city of Hamilton. At the centre of the neighbourhood are two elementary schools, one public and the other Catholic. The neighbourhood is bounded by major arterial streets that carry significant daily traffic, while in the middle of the neighbourhood, adjacent to the schools, is Lisgar Park. There are a number of other parks accessible on adjacent streets and a major regional park, Mohawk Sports Park, is located to the east of Lisgar neighbourhood.

In the spring of 2018, families at both schools were asked to complete a survey about how their kids play in their neighbourhood. Both a take-home survey and an online option were provided to parents who were encouraged to complete the questions with their children. A project engagement website was established to provide background information and updates as the project proceeded. Additional questions about how kids get to school were included.

Location of Play

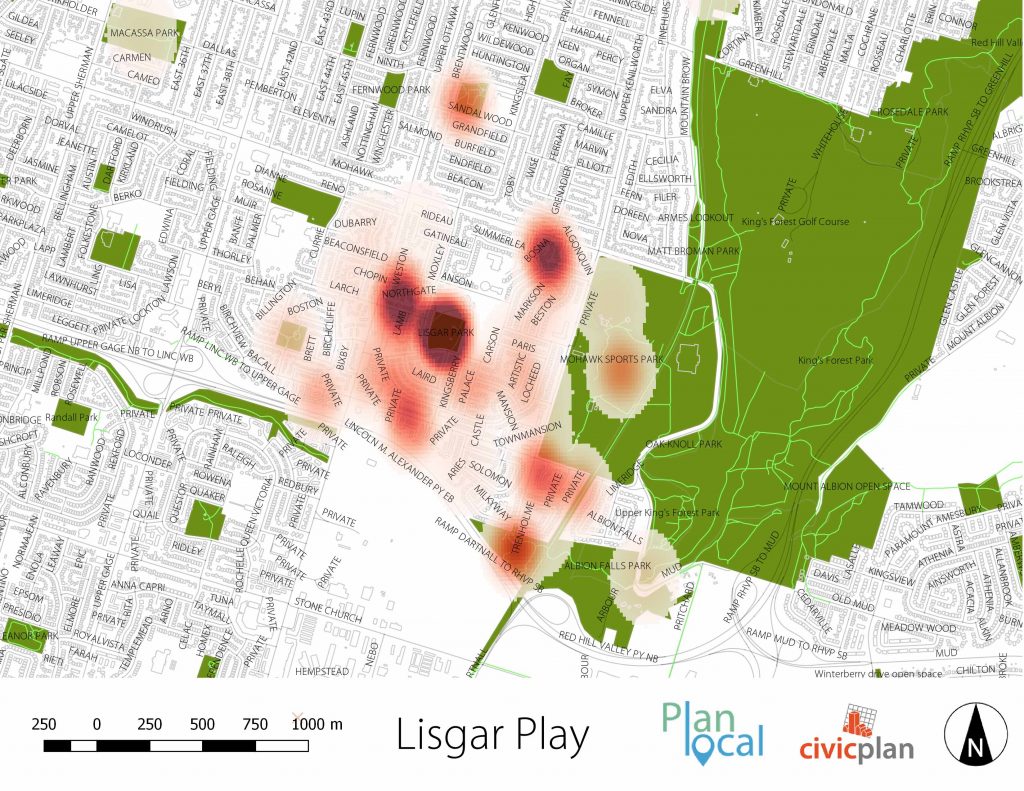

The results about the location of play offered important insights. First, locations were mapped out to determine the primary hotspots of activity. The major hotspot for play was Lisgar Park, followed by other smaller green spaces in and around the neighbourhood.

While that might not be surprising, the results reveal other interesting insights when you look at types of neighbourhood locations as a whole. In total, over 50 neighbourhood locations were recorded. Overall, the top locations for play identified by respondents were streets and sidewalks closer to home (30%). While these neighbourhood-specific locations are diffused geographically so they do not show up on the heat map, this demonstrates that streets and sidewalks themselves are important public neighbourhood spaces alongside typical recreational spaces such as a neighbourhood park. The second most identified location for play was home (27%). Lisgar Park came in third at 14% of respondents.

Type of Play

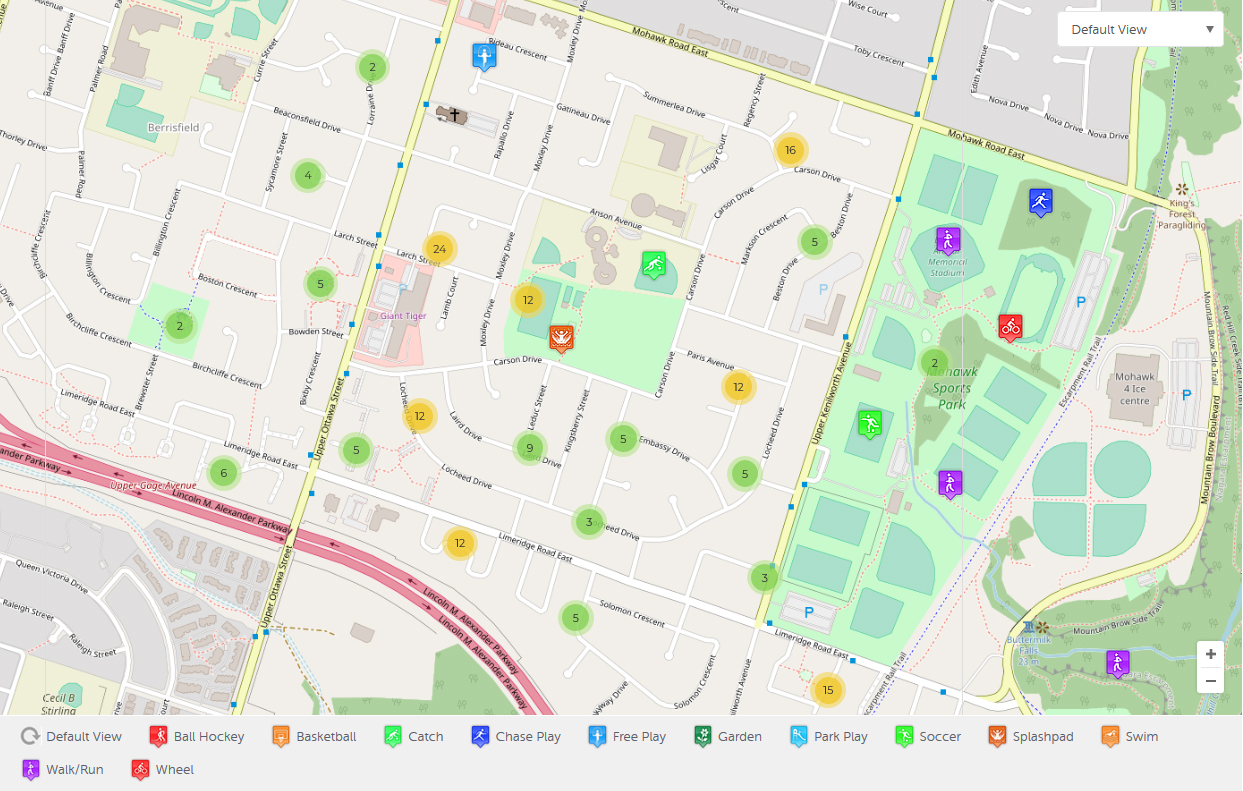

In total, over 420 activities were recorded and mapped as part of the project in over 50 neighbourhood locations. The activities were organized into 12 categories of play to give a sense of the most popular types of activity.

Coming out on top was the “Wheel” category, which includes cycling, skateboarding and scooting. It comprised 18% of activities reported. This was closely followed by general park play (at 16%), which encompasses activity on formal play structures. Third was “walk and run” in the neighbourhood, such as jogging and walking the dog (at 14%).

Two types of activities of unstructured play – running games like manhunt, tag, and hike and seek, as well as general outdoor play such as jump rope, chalking and playing with bubbles — were both at 8% of activities recorded.

Reporting Back to the Community

A key element of the pilot project was to report back to the community. As a first step, the results were posted on the project website (https://lisgar.planlocal.ca). Secondly, a printed visual summary of the results was included in take-home packages for each student in the fall of 2018. Interactive mapping showing the locations and types of play activities were provided to residents in order to help continue the dialogue about more active lifestyles in their neighbourhood.

Lessons Learned

Our first takeaway from the project was that understanding how and where a neighbourhood plays outside is an important step toward building community conversations about more active lifestyles. The pilot project was about more than recording what people are currently doing, but also about sharing these experiences and behaviour with the broader community to demonstrate easy, local options for an active lifestyle.

Second, engagement on neighbourhood play can be used to enhance community planning. For example, the fact that the most popular location for play was neighbourhood streets and sidewalks indicates that street safety should be a central issue in neighbourhood planning. When streets are observed through the eyes of children at play, planning interventions such as lower speed limits and traffic calming measures take on added importance.

Overall, the project provides an example of how play-centred engagement could be the basis for a more enhanced and responsive form of neighbourhood planning. Further, the project utilized the local elementary schools as a means to collect and distribute the results, as there were not many other structures of neighbourhood organization. Thus, future community engagement could involve the school community to facilitate conversions about a variety of neighbourhood issues, reinforcing the role of the local school as an anchor of community life.

This article was originally published in The Monitor from the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

Title photo credit: Earth Day Canada